Non-Asians Show a Growing Interest in Chinese Courses

November 29, 2006Article by Winnie Hu, The New York Times

LIVINGSTON, N.J. In the back of an Armenian church here, 2- and 3-year-olds sing along to the classic nursery tune “Frère Jacques” but this version is in Mandarin Chinese: Ni hao ma, Ni hao ma, Wo hen hao, Wo hen hao (“How are you? I’m very well.”). Afterward, they practice counting and snack on bananas, all without speaking English.

Five days a week, these toddlers attend Bilingual Buds, a Chinese-immersion preschool, where neatly printed Chinese labels are posted on everything from class bulletin boards to the bathroom sink so that parents can understand basic words.

In affluent suburban areas from New York to San Diego, children are studying second and even third languages at ages when they are still learning English. And unlike earlier times, when immigrants taught their sons and daughters their native language out of necessity or tradition, many of the families today have no personal connection to the language the children are learning. Instead, they say, they want to prepare their children for a global future and give them a competitive advantage for jobs as adults.

“I tell people that we’re going to Chinese school, and they say, ‘Why Chinese?’ ” said Carlota Beacham, 30, a dentist born and raised in Brazil who now lives in Short Hills, N.J., and spends nearly $12,000 a year to send her sons, Thomas, 4, and James, 1, to the Chinese preschool. “It sounds silly to people, but it makes sense to me because I believe Chinese will be a very important language in 20 years.”

In the past five years, foreign-language studies for the under-5 set have become as common as art and music lessons, as the more laissez-faire parenting of earlier generations is replaced by packed schedules of daily activities. But in contrast to many urban centers, where bilingual nannies may function as language tutors and formal language courses abound, suburbs seldom offer parents access to those resources.

Dissatisfied with the limited choices in classes for young children, and the occasional foreign-language story hour at their neighborhood library, highly educated, well-traveled parents are increasingly pulling together their own bilingual playgroups, which sometimes grow so popular that they expand into full-fledged programs.

Evelyn Gilbert-Bair, 37, who grew up speaking Korean with her mother, turns her home in Princeton, N.J., into a Spanish nursery for two hours every week for her 3-year-old daughter, Ellie, and three friends, collecting $15 a week from each family to buy supplies and pay a teacher. So many families expressed interest that Ms. Gilbert-Bair sent out an e-mail message last spring looking for a second teacher, only to get inquiries from even more parents.

“It wasn’t hard to start it, but I realized it was going to be a lot of work to expand,” she said, adding that she was left with the bill a few times last year after parents forgot to pay.

Similarly, Sharon Huang, 45, a former marketing executive for Weight Watchers and Nabisco, founded Bilingual Buds last year for her 2-year-old twins, Warren and Ethan, because she could not find a Chinese preschool locally like the ones she had seen when she lived in the San Francisco Bay Area. What started with 10 children in her home quickly grew to 70 students and 7 teachers, in a rented space in the church.

“The last thing I thought I would do is open up a preschool,” said Ms. Huang, who spoke Taiwanese and Japanese at home while growing up. Though she is now fluent in Mandarin, Ms. Huang’s command of that language was initially so shaky that she had to put her mother on the speakerphone to translate when she hired a Chinese nanny for her sons. The nanny now teaches at the preschool.

Researchers have shown that a child who learns a foreign language during a so-called “sensitive period” before puberty is more likely to speak it as a native does, though they disagree over whether the reason is biological or social.

“There is not any such thing as too young,” said Lisa Davidson, an assistant linguistics professor at New York University. “It’s a gradient scale. The younger you are, the more likely you are to become proficient.”

Many parents who are aware of the importance of early language training but cannot teach their own children have sought out established enrichment programs like the Manhattan-based Language Workshop for Children, which has 800 students under 5, more than half of whom are enrolled outside Boston, on Long Island or in northern New Jersey.

In response to demand, another program, Italian for Toddlers, has expanded since 2004 from a brownstone on the Upper West Side to branches in Pelham Manor, N.Y., and Greenwich, Conn. A third of its 300 students are under 2.

Still, it is not enough.

“Do you know how many Anglo families are putting their kids in front of ‘Dora’?” said Deborah J. Chitester, a bilingual speech pathologist, referring to the cartoon “Dora the Explorer,” which has passages of conversational Spanish. Ms. Chitester, who formed three Spanish playgroups in June in Lawrenceville, N.J., added that parents were also racing to stores for books in Spanish.

In Riverside, Conn., about two dozen parents organized a Chinese-language school in 2002 after becoming dissatisfied with the traditional teaching methods at a local school for Chinese-Americans. The Chinese Language School of Connecticut now has 220 students in its Sunday classes, nearly a third of them under 5.

Susan Serven, 42, one of the school’s founders, said the parents had developed an interactive curriculum, using puppets and playing games like Twister and Jeopardy in Mandarin. Ms. Serven, who adopted two girls from China, said that many of the families are mixed racially and ethnically, and see the language as not only an investment in the future but also a way to preserve their children’s heritage.

It is that connection to the past that propels parents like Faith Tissot, 35, a nurse, to keep up with the costly and time-consuming lessons. Mrs. Tissot, whose 18-month-old daughter, Juliette, takes French in Roslyn Heights, N.Y., said her husband, Marc, an anesthesiologist, was from the family of the 19th-century French painter James Tissot.

“She’s an open canvas; she just soaks it up like a sponge,” Mrs. Tissot said. “And it’s part of her bloodline.”

LIVINGSTON, N.J. In the back of an Armenian church here, 2- and 3-year-olds sing along to the classic nursery tune “Frère Jacques” but this version is in Mandarin Chinese: Ni hao ma, Ni hao ma, Wo hen hao, Wo hen hao (“How are you? I’m very well.”). Afterward, they practice counting and snack on bananas, all without speaking English.

Five days a week, these toddlers attend Bilingual Buds, a Chinese-immersion preschool, where neatly printed Chinese labels are posted on everything from class bulletin boards to the bathroom sink so that parents can understand basic words.

In affluent suburban areas from New York to San Diego, children are studying second and even third languages at ages when they are still learning English. And unlike earlier times, when immigrants taught their sons and daughters their native language out of necessity or tradition, many of the families today have no personal connection to the language the children are learning. Instead, they say, they want to prepare their children for a global future and give them a competitive advantage for jobs as adults.

“I tell people that we’re going to Chinese school, and they say, ‘Why Chinese?’ ” said Carlota Beacham, 30, a dentist born and raised in Brazil who now lives in Short Hills, N.J., and spends nearly $12,000 a year to send her sons, Thomas, 4, and James, 1, to the Chinese preschool. “It sounds silly to people, but it makes sense to me because I believe Chinese will be a very important language in 20 years.”

In the past five years, foreign-language studies for the under-5 set have become as common as art and music lessons, as the more laissez-faire parenting of earlier generations is replaced by packed schedules of daily activities. But in contrast to many urban centers, where bilingual nannies may function as language tutors and formal language courses abound, suburbs seldom offer parents access to those resources.

Dissatisfied with the limited choices in classes for young children, and the occasional foreign-language story hour at their neighborhood library, highly educated, well-traveled parents are increasingly pulling together their own bilingual playgroups, which sometimes grow so popular that they expand into full-fledged programs.

Evelyn Gilbert-Bair, 37, who grew up speaking Korean with her mother, turns her home in Princeton, N.J., into a Spanish nursery for two hours every week for her 3-year-old daughter, Ellie, and three friends, collecting $15 a week from each family to buy supplies and pay a teacher. So many families expressed interest that Ms. Gilbert-Bair sent out an e-mail message last spring looking for a second teacher, only to get inquiries from even more parents.

“It wasn’t hard to start it, but I realized it was going to be a lot of work to expand,” she said, adding that she was left with the bill a few times last year after parents forgot to pay.

Similarly, Sharon Huang, 45, a former marketing executive for Weight Watchers and Nabisco, founded Bilingual Buds last year for her 2-year-old twins, Warren and Ethan, because she could not find a Chinese preschool locally like the ones she had seen when she lived in the San Francisco Bay Area. What started with 10 children in her home quickly grew to 70 students and 7 teachers, in a rented space in the church.

“The last thing I thought I would do is open up a preschool,” said Ms. Huang, who spoke Taiwanese and Japanese at home while growing up. Though she is now fluent in Mandarin, Ms. Huang’s command of that language was initially so shaky that she had to put her mother on the speakerphone to translate when she hired a Chinese nanny for her sons. The nanny now teaches at the preschool.

Researchers have shown that a child who learns a foreign language during a so-called “sensitive period” before puberty is more likely to speak it as a native does, though they disagree over whether the reason is biological or social.

“There is not any such thing as too young,” said Lisa Davidson, an assistant linguistics professor at New York University. “It’s a gradient scale. The younger you are, the more likely you are to become proficient.”

Many parents who are aware of the importance of early language training but cannot teach their own children have sought out established enrichment programs like the Manhattan-based Language Workshop for Children, which has 800 students under 5, more than half of whom are enrolled outside Boston, on Long Island or in northern New Jersey.

In response to demand, another program, Italian for Toddlers, has expanded since 2004 from a brownstone on the Upper West Side to branches in Pelham Manor, N.Y., and Greenwich, Conn. A third of its 300 students are under 2.

Still, it is not enough.

“Do you know how many Anglo families are putting their kids in front of ‘Dora’?” said Deborah J. Chitester, a bilingual speech pathologist, referring to the cartoon “Dora the Explorer,” which has passages of conversational Spanish. Ms. Chitester, who formed three Spanish playgroups in June in Lawrenceville, N.J., added that parents were also racing to stores for books in Spanish.

In Riverside, Conn., about two dozen parents organized a Chinese-language school in 2002 after becoming dissatisfied with the traditional teaching methods at a local school for Chinese-Americans. The Chinese Language School of Connecticut now has 220 students in its Sunday classes, nearly a third of them under 5.

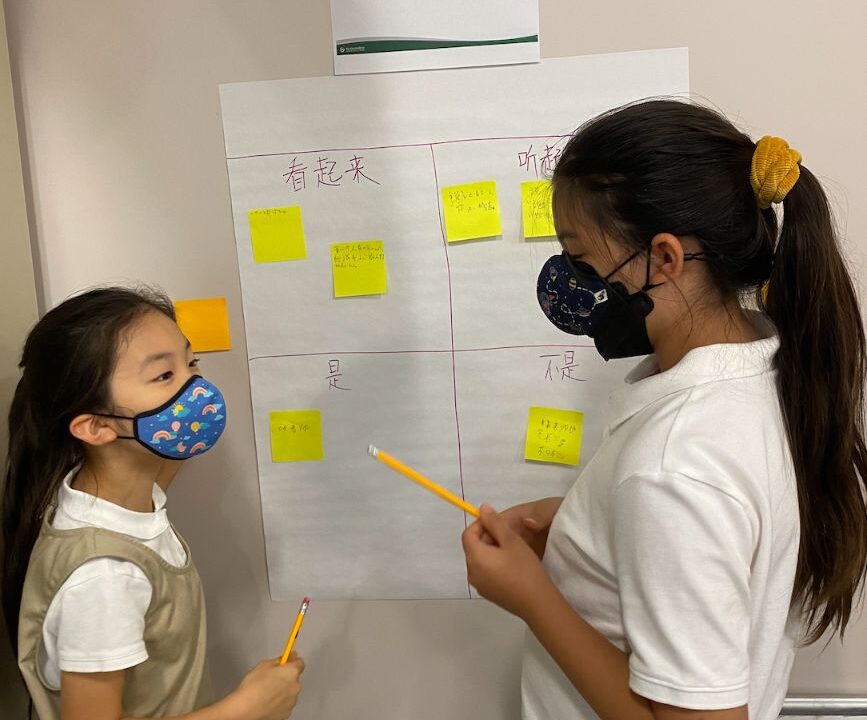

Susan Serven, 42, one of the school’s founders, said the parents had developed an interactive curriculum, using puppets and playing games like Twister and Jeopardy in Mandarin. Ms. Serven, who adopted two girls from China, said that many of the families are mixed racially and ethnically, and see the language as not only an investment in the future but also a way to preserve their children’s heritage.

It is that connection to the past that propels parents like Faith Tissot, 35, a nurse, to keep up with the costly and time-consuming lessons. Mrs. Tissot, whose 18-month-old daughter, Juliette, takes French in Roslyn Heights, N.Y., said her husband, Marc, an anesthesiologist, was from the family of the 19th-century French painter James Tissot.

“She’s an open canvas; she just soaks it up like a sponge,” Mrs. Tissot said. “And it’s part of her bloodline.”